With 2015 officially a lost cause, it’s time to start thinking about 2016. Not because it beats watching a bullpen with one reliable arm that’s been worked to the point of not being reliable anymore try to get nine or more outs every night. Or not just because of that. No, if 2015 has any utility at this point beyond the comfort of having baseball available as a soundtrack to our respective summers, it’s the ability to evaluate players and test them at positions in ways that are not possible for a team that actually needs to win games.

To leverage this time properly, however, it’s necessary to have hypotheses about the construction of the 2016 roster to test. We don’t need to allocate playing time to De Aza, for example, because it’s extremely unlikely he’ll be around next year. Seeing what we have at this point in time in Bradley Jr and Castillo, on the other hand, is enormously important to the planning for next year.

Here then is the roster I would assemble for next year. Playing time for the rest of this year would be dictated by this projection, with those in the plans receiving the playing time with everyone else getting spot starts here and there where rest is necessary.

To be clear, this is what I would do, not what I expect the front office to do. Or at least not entirely. Given the two consecutive last place finishes, the front office may not be able to take the chances necessary to commit to the roster below, and they’re required to cope with variables such as egos and contracts that those of us who do our planning on paper do not. Because the positional players will impact the pitching staff, we’ll start with them.

Infield

In general, the Red Sox have the potential for an above average infield offensively, with defense questionable at the corners but solid at worst up the middle. Much depends on whether the club decides to pull the ripcord on their largest recent free agent deals, but given the cost of moving either Ramirez or Sandoval with the dollars attached to both and the potential for a rebound in both cases, I would not. Onto the specifics.

Designated Hitter

Starter: Ortiz

Backup: Ramirez

Depth: Shaw (AAA)

Not much to debate here. Ortiz’ option for next year has been triggered, he cannot be traded without his consent and has stated he will not accept a trade, and has recovered from a very slow start to post a .263/.351/.506 line, good for a 130 OPS+. He’s still having problems with left-handed pitchers, but the problem is far less acute than it was at the start of the year.

Besides, how he has performed to date is relatively academic. Argument about whether Ortiz should or should not be the DH next year are irrelevant: he will be, by virtue of his contract and his stature with the club.

Catcher

Starter: Vazquez

Backup: Hanigan

Depth: Swihart (AAA)

It’s somewhat surprising in this trainwreck of a season given the periodically horrific struggles of the pitching staff – it cost Nieves his job, remember? – that more isn’t made of the loss of Christian Vazquez to injury. As well regarded as he is defensively, and he is very well regarded indeed with one AL West club apparently considering him the best defensive catcher in the league, it would be absurd to try and make the argument that the problem with our pitching has been the catching staff. The pitching staff, bullpen and rotation both, is short of talent.

But it’s just as nonsensical to lament the state of the pitching and not acknowledge the impact of the loss of Vazquez. Everyone remembers the obvious incidents such as Leon having Tazawa throw a 3-0 fastball right down the pipe to Alex Rodriguez, who promptly deposited the pitch over the fence. It’s harder to consider the impact of the loss of Vazquez’ pitch-framing skills.

Metrics vary, and debates over the precision of pitch-framing persist, but it’s safe to say that any borderline strikes a catcher can steal for his pitcher are a good thing. And Vazquez steals them about as well as anyone in the game.

Neither Hanigan nor Swihart is exceptionally bad at framing, exactly. Two seasons ago Hanigan was in the Top 10 in the league at the art, though he’s down to 51 by BP’s numbers this season. Swihart has fared a bit better this season, placing 19th in the number of total strikes stolen and well ahead of that on a rate basis.

Neither is in Vazquez’ league, however. According to BP, for example, in 3499 framing opportunities this season, Swihart has stolen just under 20 strikes. Last season, in 429 fewer chances Vazquez stole just under 95 strikes. It’s impossible to make the argument that this year’s pitching staff would not have benefitted from the 85 or so balls that Vazquez would have turned into strikes. It’s just difficult to know how much.

Given that even in a best case scenario, we’re not turning over the entire pitching staff then, I would want to maximize the performance of the pitching that I do have. Which means making Vazquez the primary catcher, assuming he’s recovered sufficiently from Tommy John surgery.

Because he’s far from established offensively, however – he put up an OPS+ of 75 in 2014 – you want his backup to be somewhat capable offensively. Hanigan’s no star with an OPS+ this season of 81, but he at least gets on base at a reasonable clip (.348 OBP this season). Swihart would doubtless be less than thrilled at being returned to AAA next season, but he’d get some seasoning and doubtless be up soon given the fact that Vazquez is coming off major surgery and Hanigan has played more than 100 games once in nine years.

In a perfect world, Swihart becomes at least a poor man’s Vazquez when it comes to framing. If this were to happen, you’d take the slight hit in defensive ability in return for Swihart’s far greater offensive upside, and use Vazquez as a potentially significant trade chip.

Until then, however, the pitching staff needs all the help it can get, which means Vazquez stays.

First Base

Starter: Ramirez

Backup: Holt

Depth: Shaw (AAA)

Chad Finn, as he so often does, already summed this up better than I can so just go read his piece. For those that want a summary, it’s pretty simple. Ramirez is a trainwreck in left. He might be a trainwreck at first, and you have to consider Butterfield’s comments about the underappreciated difficulty and impact of the position, but at least he has history playing the infield. Removing Ramirez from the outfield also allows you to roll out an entire outfield of above average defenders, but we’ll get to that. Worst case, you survive him at first for a season, hope Ortiz retires after next season 500 home runs in hand and you put him where he can’t do any harm on the field: DH.

There are other options, but none are particularly attractive. Free agency, from Chris Davis to a return of Mike Napoli, would require the club both pay a free agent premium and be willing to accept some boom or bust risk. As for in house candidates, Travis Shaw is a great story at the moment, and it’s to his credit that he’s making the most of his opportunity, but we’re still talking about a player with a .256/.319/.395 line in 158 games at AAA. If the Red Sox have some reason to suspect his current performance is sustainable, be it a swing change or similar, so be it. Otherwise, virtually nothing in his minor league track record suggests that he should be handed the starting job. Keeping him at AAA for depth reasons, and to prove that this second half performance is not a fluke, is the smart play.

In short, moving Ramirez to first base both addresses a potentially gaping roster hole for next year and allows the club to rectify its mistake in attempting to live with a compromised outfield defense. The Red Sox decision on this is particularly important, because while the club has stated it will not play Ramirez at the position in 2015, he should be playing it at least part time.

The Red Sox saw what happened when he attempted to learn a new position on the fly this season, and it helped cost them games. If it’s going to do the same at first base, it would be nice if the games lost to his training didn’t matter.

Second Base

Starter: Pedroia

Backup: Holt

Depth: Marrero (AAA)

As with DH, not much debate here. Barring some inconceivable trade, Pedroia will be the Red Sox second baseman in 2016. It will be an unusual offseason, however. For the past several seasons, there was a great deal of debate as to whether Pedroia’s depressed offensive numbers were a sign of inevitable decline or more attributable to two years of hand and wrist injuries. His 2015 campaign to date suggests it was more of the latter. His numbers certainly are not what they were during his MVP peak, but they’re solidly above average for the position.

But the aspects to his play we’re used to taking for granted in spite of the ups and downs of his offense, his defense and baserunning, have taken hits this season. Given his age, and the hamstring issue that has put him on the DL twice this year, then, the Red Sox will for the first time in years have cause to question what they’re going to get defensively out of second base.

Third Base

Starter: Sandoval

Backup: Holt

Depth: Shaw (AAA)

There is no getting around the fact that Sandoval’s first year with the Red Sox has been a disaster. By Fangraphs WAR metric, Sandoval has been worth -1.3 wins. For $17M this year, then, the Red Sox have gotten a player who’s below replacement level. Offensively, his strikeout rate is up, and his walk rate, average, on-base and slugging percentages are all down. Which is bad. His defense has been amongst the worst in the league at the position, which is worse. Virtually the only consolation is that the player he replaced – Will Middlebrooks – was even worse, with a .212/.241/.361 line that got him sent back to the minors again while just shy of being 27.

The Panda’s been bad, in other words. Really, really bad. The question is what to do? Some have suggested throwing in a sweetener and trading him for another bad contract such as James Shields. But the question here is whether you believe this is really his new level of ability. Whether Sandoval has, in a single season at the age of 29, eroded from a slightly above average offensive and defensive performer – albeit with a problematic trajectory – to a below replacement level player.

Personally, that seems less than likely, and coupled with the lack of a real alternative – unless you think Shaw is a starting third baseman for a first division team – I’d sent him to what used to be known as the Athlete’s Performance Institute this offseason and hope for a bounceback. Best case, you get the player you thought you were getting and don’t have to both plug the third base hole and eat another bad contract. Worst case, his performance level is similar and your bargaining position is slightly improved by the fact that there’s less money for a trading partner to take on.

Shortstop

Starter: Bogaerts

Backup: Holt

Depth: Marrero (AAA)

Perhaps the easiest decision on the field, Bogaerts is your shortstop for 2016 – much to the chagrin of sportswriters who enjoyed milking the “revolving door at shortstop” metaphor. Though his value at present is heavily batting average driven, count me among those who believe that his power will come. After a hot start last year, he fell into such a hole that some questioned whether he’d ever make enough contact to be a starting shortstop, let alone live up to the hype that accompanied him as a prospect. This season’s adjustments have seemingly answered those questions; my suspicion is that after another offseason, he’ll be in a better position to know when to look for pitches he can drive.

Even more impressive than his offensive improvement last season to this has been his play in the field. He’ll never be Iglesias or even, probably, Marrero, but the questions about whether Bogaerts can play the shortstop position at the major league level have essentially ended. He’s smoother, more confident and more intelligent on defense, and the total package he’s bringing to the table at present has him as the fourth most valuable shortstop by WAR in baseball.

Power and walk rate questions notwithstanding, that’s a starter.

Outfield

According to Peter Gammons, Cherington “has singled out defense as his primary focus on improving his team,” which means extended looks for Castillo and Bradley. As discussed above, the simplest mechanism for improving the outfield defense is removing Ramirez from it. Even if the Red Sox were to substitute a replacement-level talent, it would be a significant net win. The Red Sox, however, do not have to replace Ramirez with a replacement-level talent: they can legitimately field an outfield of three center-fielders. Here’s how I would deploy them.

Left Field

Starter: Castillo

Backup: TBD/Holt

Depth: Margot (AA)

Castillo is funny in a way. First the writers buried the front office for being patient and stashing him in AAA. Then the writers buried the front office for signing him to a $70+ million contract, having concluded after a hundred and fifty at bats or so that he was not a major league player. Then, having finally been granted regular at bats in the majors, he’s put up a .339/.369/.548 line in a very small sample of second half at bats and writers swung back the other way.

What Castillo is offensively remains to be seen, and will likely be scrutinized heavily over the last month and a half. Defensively, however, he’s an immediate and major upgrade over Ramirez in left, with the capability to shift to center or right as needs warrant. If you assume that some of his initial struggle is attributable to the adjustment from moving from Cuba to the US, and to his substantial layoff from live baseball, it’s certainly reasonable to assume Castillo is better offensively than the .282/.337/.385 he put up in AAA. So even if his second half surge is unsustainable, a midpoint between the two – say a .350ish OBP with .450 power – would make him enormously valuable.

Center Field

Starter: Bradley Jr

Backup: TBD/Holt

Depth: Margot (AA)

The case for Jackie Bradley Jr in center is that he is the best defensive centerfielder in the majors. The case against Jackie Bradley Jr in center is that even with his second half explosion he is the owner of a .204/.282/.312 line over 600+ plate appearances in the major leagues. Even with his transcendent defense, that won’t play. The question then is what’s more representative of his true offensive level: the 65 lifetime major league OPS+ or this year’s 126? The .593 OPS lifetime major league OPS or the .851 OPS over 1300 minor league plate appearances?

I’ve always been inclined towards the latter, in both cases. I was not in favor of his promotion out of spring training in 2013, his Ruth-like numbers notwithstanding. The premature promotion obviously isn’t solely to blame for his struggles since, but it certainly didn’t help. But with the rare exception, Bradley Jr always performed in the minors, so I’ve had faith.

It’s probably not reasonable to expect him to be throwing up multiple double and home run games regularly, but as Matthew Kory documents, there are mechanical reasons to expect that some aspect of his performance is not a simple small size artifact. If this is true, and the next month and a half should give us more evidence one way or another (although September’s data is less valuable due to callups), he’s my center fielder next season. Yes, over Mookie.

There is certainly precedent for young centerfielders prematurely exposed to the major leagues to struggle for several years before finding their footing – see Gomez, Carlos. Bradley Jr may not be likely to follow that path offensively, but he doesn’t have to. He just needs to hit enough to carry that glove.

Right Field

Starter: Betts

Backup: TBD/Holt

Depth: Margot (AA)

Larry Lucchino has traditionally been fond of saying that the Red Sox need two centerfielders given the dimensions of Fenway: one for center, and another for right. I’d keep Mookie playing centerfield, therefore, I’d simply have him do that from rightfield. And ideally, from now through the rest of the season.

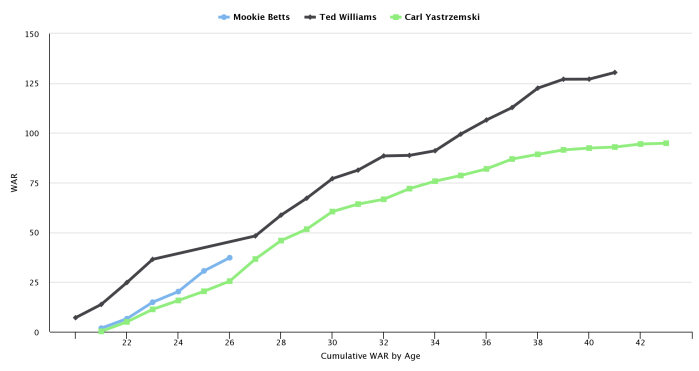

Shifting him to right has nothing to do with Mookie’s play. While he took some lumps early as expected, he’s putting up a .270/.320/.438 (104+ OPS) line as a 22 year old while playing well above average defensively. As measured by WAR, in fact, Betts has been a tick more valuable than Bogaerts, in spite of the latter’s much higher profile season. Playing Betts in right instead is about the value of Jackie Bradley Jr’s defense in center. If you have the best centerfielder in the majors, it doesn’t make much sense to keep playing him in right.

Not that it matters much in the bigger picture, as well, but Betts bat profiles better in right than does Bradley’s. The only argument for playing Bradley in right over Betts, in fact, is JBJ’s prodigious arm strength. That’s not enough for me, however, to forestall the change.

Think about the ground a Castillo/Bradley Jr/Betts outfield could cover. Too bad it won’t happen.

Rotation

As measured by xFIP, the Red Sox starters are 16th out of 30 clubs. WAR, 18th. K/9, 19th. BB/9, 24th. ERA, 28th. If you’ve watched the games this year, none of these numbers are likely to come as a surprise. The starters pitched so badly they got a coach fired, and fared poorly enough under the second that one got released and another came down with a very conveniently timed “injury.”

To be fair to the pitching, some of this isn’t their fault – note the big delta between their xFIP and ERA. With third base and left field defensive black holes, some regression from second base, the occasional learning mistake in centerfield, the season-long absence of a truly excellent defensive catcher and inconsistent play all over the diamond, it’s not surprising that the Red Sox starters struggled.

The defense notwithstanding, of course, the rotation entering the season was short on talent. Buchholz has the ability to pitch like one of the best pitchers in the league, and indeed was better than departed ace Lester on a rate basis, but his track record suggested he wouldn’t pitch like that for a season, which he did not. Porcello has massively struggled in his first year in Boston, to the point that he’s been hidden in the minors. Masterson is gone, and his career may be in jeopardy as his effectiveness without plus velocity is minimal. Miley’s first month or so was horrific, and while he’s righted the ship since he’s essentially a league average innings eater. As for Joe Kelly, well, there may be no bigger enigma in the game. It’s difficult to recall someone who throws that hard, that effortlessly, and yet gets hit that hard.

But that’s the 2015 rotation: what does 2016’s look like?

A lot like 2015’s, in all probability. You might plan for a Buchholz absence, but the combination of his risk-limiting options and his ability to give you elite innings make him a keeper. Porcello is likely immovable, and just as likely to bounce back to previous levels of ability, so he’s in the rotation. As is Rodriguez, after an offseason of stripping his delivery of tells. If you can get something useful for Miley, who has pitched better of late and is signed to a very reasonable deal, I’d consider it, but otherwise, he’s back as well. Which leaves us with a rotation, in no particular order, of:

- Buchholz

- Rodriguez

- Porcello

- Miley

What you do with the fifth spot and whether you’re more motivated to move Miley depends in part on what you see down the stretch from Owens. Given that the club will be coming off of two last place finishes in a row, predictability will be at a premium, so Miley sticks around for me.

Which leaves one opening in the rotation, with Owens/Johnson/Wright as depth starters. Unless, of course, one of them is traded to plug that hole in the rotation. While I’m less sold on the need for an ace than most writers, adding a high upside arm is something the Red Sox should pursue in the offseason. Importantly, this doesn’t mean handing Cueto or Price better than $200M on the open market: I’d go harder after the Carrascos of the world with a package built around pieces like Owens, Margot, Devers and so on. Rodriguez would be off limits, but every other starter in the system with the exception of Anderson Espinoza would not be.

If the 2016 rotation was:

- Carrasco (or similar)

- Buchholz

- Rodriguez

- Porcello

- Miley

- Johnson/Wright/etc

That plays for me. Particularly because you can always trade for more pitching in season if need be, in rental form or otherwise.

And before you ask, yes, Kelly’s omission is intentional.

Bullpen

People look at the bullpen today and think: what the hell happened? How did we get to the point that we have basically one reliable arm in Tazawa? Or had, before we leaned on him too heavily. The answer, to a degree not often acknowledged by the writers, is injury. If Workman, for example, isn’t lost to Tommy John, the bullpen looks very different. Same with Varvaro, whose ineffectiveness, it would appear, was related to the fact that he also required Tommy John. If those two aren’t lost more or less out of the gate, we might not see Ogando pitch so many meaningful innings and give up so many meaningless home runs.

Mujica, admittedly, was a total loss: after some initial, exasperating success, he’s been worse with Oakland than he was with Boston (71 ERA+ vs 93). Breslow has also been dead money, though it was interesting to see him come close to blaming his performance on Farrell’s usage to the Globe. It’s also true, as has been pointed out repeatedly, that the Red Sox have failed to draft and develop bullpen arms. Maybe Barnes and Light get there by next year, but there are significant questions at this point attached to both.

But the core of next year’s bullpen is likely already here.

- Uehara

- Tazawa

- Kelly

- Workman

- Varvaro

- Barnes

- Layne

- Machi

- Ross

- Cook

Some, or maybe most of those arms, will be hurt, ineffective or both. Which means that the Red Sox will need to spend the offseason acquiring other potential bullpen pieces, preferably ones that throw hard given the game’s direction. Whether that’s via trade, waiver pickups, the Rule 5 draft as with Baltimore or even potentially free agency is less important than the club getting to spring training next year with twice as many arms as they’ll need.

Unless you’re some sort of wizard, the most effective approach to building bullpens is via a shotgun.